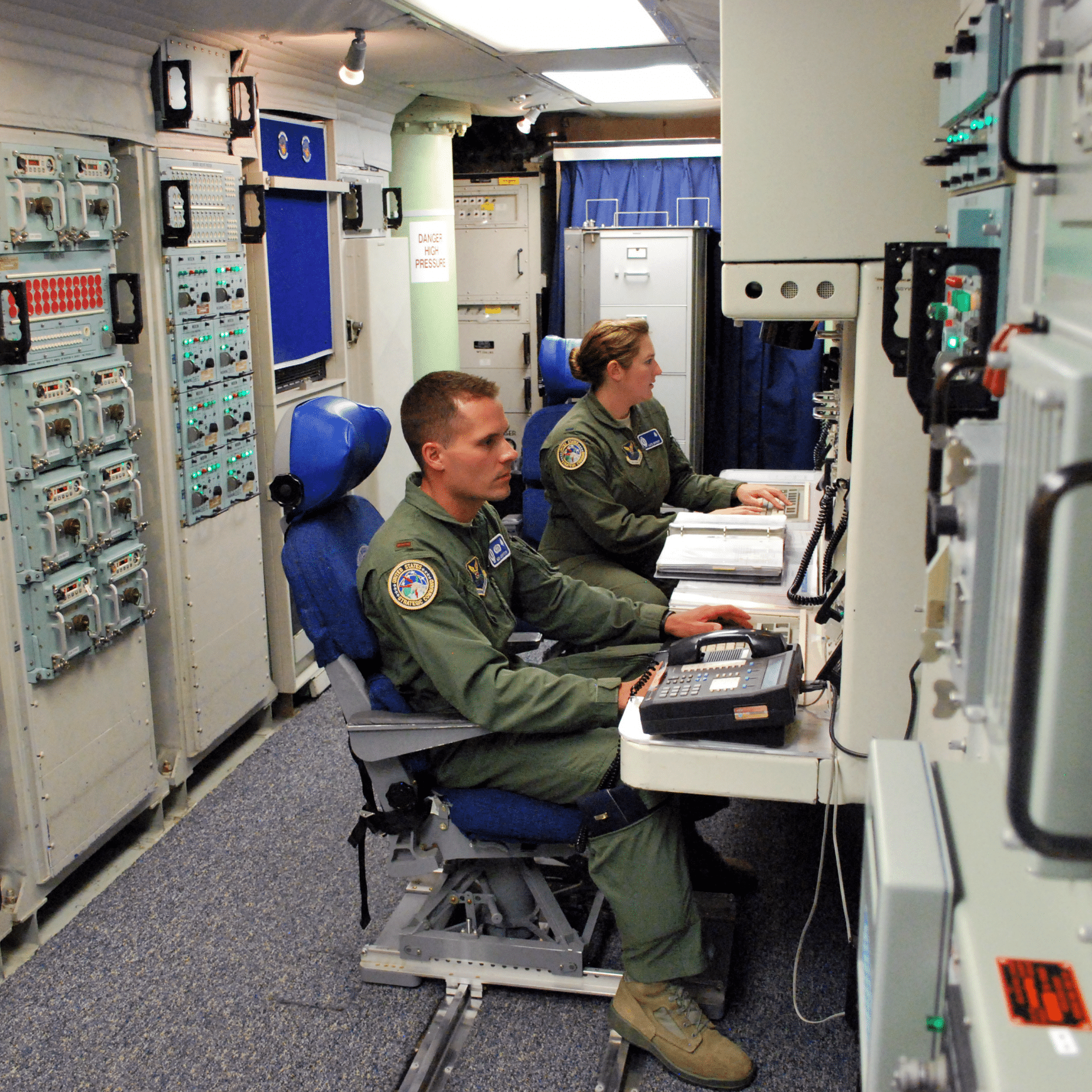

More than 2,400 miles of pressurized cable connect the facilities in Montana's missile field alone. (Chris Willis / US Air Force)

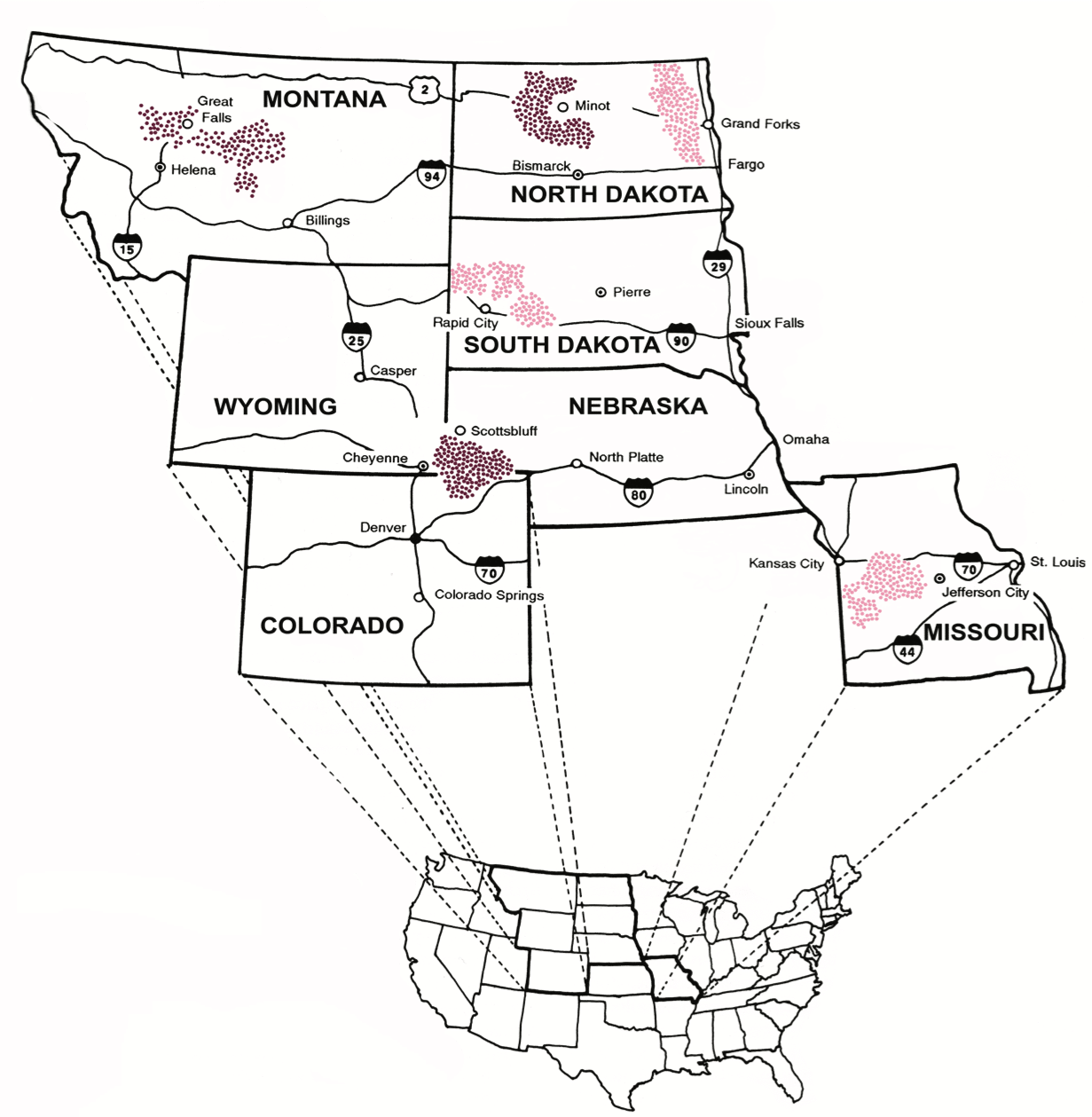

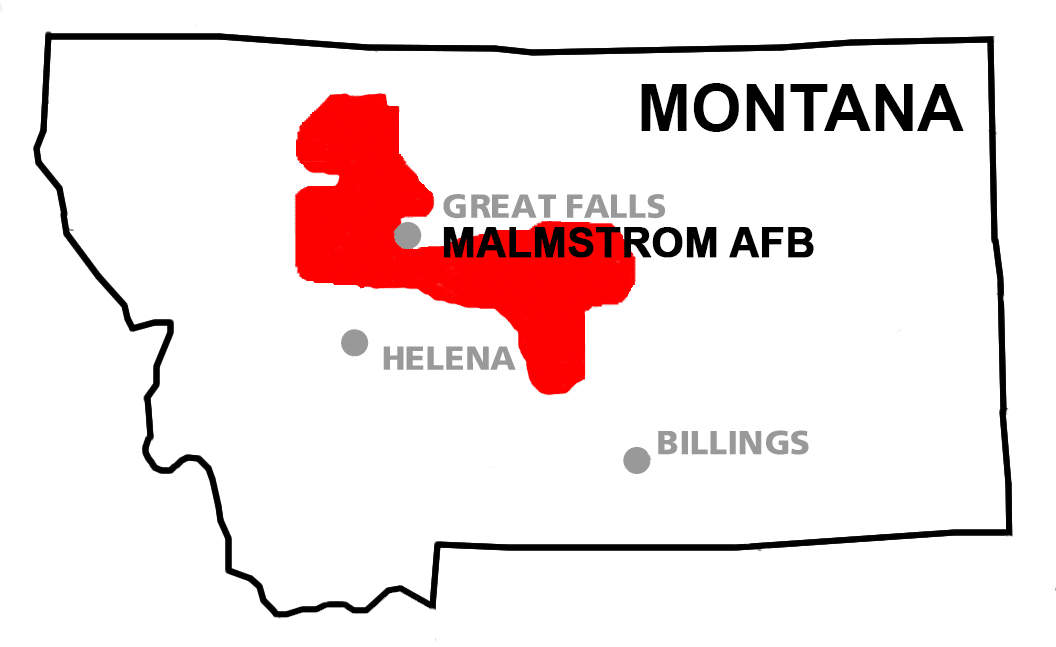

The three missile wings are headquartered, respectively, at Malmstrom Air Force Base in Great Falls, Montana; Minot Air Force Base, just north of Minot, North Dakota; and F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Cheyenne, Wyoming. The Warren missile complex extends into Nebraska and Colorado. The Montana missile complex, which is the most spread out, covers 13,800 square miles, more territory than Maryland. There are missile silos in the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest and the Pawnee National Grassland. There are 12, plus a launch control facility, on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, home of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara nations. There are missile silos next to homes, farms, and schools.

There are currently three active ICBM missile wings in the United states, spread across five states. Each dot represents a missile site. Those in darker red are active silos; pink ones are decommissioned. (Nukewatch)

A sense of how spread out the missile fields are is important to understanding how embedded they are in local economies. Shane Etzwiler is president of the Great Falls Chamber of Commerce, and I met with him and County Commissioner Briggs in July at the chamber, located on a pandemic-quieted downtown street. Etzwiler lives 35 miles east of Great Falls in Fairfield, a community of some 700 people with spectacular views of the Rocky Mountain Front. Airmen bound for the launch control facility known as Hotel 1 pass through Fairfield. “They’re stopping in communities and they're buying the drinks, buying the to-go because they're going to be in the hole,” Etzwiler said. In Fairfield, “that restaurant will have 24 or 36 airmen stop in, getting to-go orders or coming out of the field ready for a different meal. The impact is tremendous in our area.” In the early teens, the Pentagon made plans to remove 50 nuclear missiles to comply with New START. Legislators from the “missile caucus” states swung into action, and in January 2014, Republican North Dakota Senator John Hoeven attached an amendment to a major spending bill that denied the Defense Department the funds it needed to begin making cuts. When, a month later, members of the missile caucus got wind that the Defense Department was going ahead with an environmental assessment on eliminating missile silos, they drafted outraged bipartisan letters to the defense secretary. One, signed by senators from Montana and North Dakota, read: "We write to make very clear our strenuous opposition to any attempt by the Department of Defense to circumvent existing law to proceed with an Environmental Impact Study or an Environmental Assessment on the elimination of Minuteman 3 silos.” The Pentagon put the assessment on hold and came up with a scheme to remove the 50 missiles from silos across all three missile wings, rather than taking out a whole squadron from a single Air Force base. The Pentagon also said it would keep the empty silos “warm,” meaning maintained and ready to use. Lawmakers from the missile caucus applauded; Democratic Sen. Jon Tester of Montana called it “a big win for our nation’s security and for Malmstrom Air Force Base and north-central Montana.”

“The town treated the base almost like a cargo cult object, in that it fell from the sky and brought great prosperity.”

He was right on at least one point: Maintaining the silos would bring some medium-term financial gain to north-central Montana. The military—Malmstrom Air Force Base and the Montana Air National Guard—accounts for a third of the regional economy, with another third coming from agriculture and a third from everything else. Malmstrom alone is one of the region’s largest employers. The base had an economic impact of $372 million in 2019, including direct and indirect jobs as well as expenditures on construction and other services. It’s intertwined with city life in other ways, too. “Malmstrom brings a diversification into our community that we wouldn't have otherwise,” said Briggs. “If you look around Great Falls, we've got amenities that cities twice our size don't have. A symphony.” Kristen Inbody, a writer who works for Benefis Health System in Great Falls, credited Malmstrom as a tool of desegregation, and for making Great Falls the most racially diverse city in Montana. Inbody grew up in Choteau, a town surrounded to the east, south, and west by 20 missile silos. “In real life, in everyday life, it’s good roads and a better economy than there would be otherwise,” she said. She is conscious of the devastating effect a nuclear strike on her region would have. “People don’t think it’s going to happen,” she said. “The chatter is way more often about Yellowstone.” She referred to the supervolcano under Yellowstone National Park, 300 miles away, which last erupted 70,000 years ago. “The town treated the base almost like a cargo cult object, in that it fell from the sky and brought great prosperity,” said former missileer Bosetti. Case in point: Malmstrom decommissioned its runway in 1997 because no fixed-wing aircraft used the base anymore, and the runway was expensive to maintain. Ever since, local business and political leaders have tried to bring a mission to Malmstrom that would reopen the runway—and rejected other, potentially lucrative investments near the base, including a housing development, that might interfere with theoretical future runway use. During his time in Great Falls, Bosetti said, a major shipping company wanted to open a sorting center near the runway. “That would have been amazing. Look at the growth of shipping and delivery,” he said. But “the town got really mad and said, ‘No, no, no, the planes are coming back. We can't build this thing because it'll stop the tanker wing from relocating here eventually in the future.’ It never did. It never will.” As recently as 2019, Montana Republican Rep. Greg Gianforte attached language to a defense bill directing the Air Force to consider improvements to mothballed facilities like the Malmstrom airstrip. “With some work, the base’s runway can once again host flying missions,” Gianforte said in a speech. The air strip may be a lost cause, but for today’s city boosters, nuclear weapons hold economic promise. Greater Great Falls can expect to host a third of the 600-plus GBSD missiles the Air Force is having built. The Air Force plans to begin GBSD-related construction around Cheyenne in 2023, Great Falls in 2026, and Minot in 2029. Launch control facilities will be upgraded. The special vehicles that move the missiles, known as transporter erector loaders, might clock in at a different size or weight than the current ones, requiring updates to county roads. “We're talking infrastructure and roads and bridges and things like that,” Etzwiler said. “They need project managers, they need warehousing, they need skilled trade workers and electronics, telecom, you name it.” It all means more jobs. “We're excited,” he said.

Previous models of intercontinental ballistic missiles are displayed at the National Museum of the United States Air Force near Dayton, Ohio. The Minuteman III (visible at the center right of this photo, with first and third stages painted green) is the only American ICBM deployed today. (USAF Museum)

A nuclear bomb without a delivery device is a bullet without a gun. The Americans used airplanes to drop the first atomic weapons in 1945, but soon both Washington and Moscow sought other means of delivery, something that could launch the explosive all the way from home turf to foreign soil. Nazi Germany’s V2 rocket served as inspiration. After World War II, the Soviet Union took possession of the V2 test range and factory, but the United States got its hands on the rocket’s inventor, Wernher von Braun, and brought him to America. US nuclear missiles followed, with the first, the Atlas, entering service in 1958. In addition to the Titan and Peacekeeper, there were the Jupiter and Snark, the last so-named after the elusive prey in the Lewis Carroll poem “The Hunting of the Snark.” In the words of a publication from Los Alamos National Laboratory, a warhead must be able to “survive and function while traveling through multiple severe environments: the extreme violence of launching; accelerating within seconds to Mach 23 (about 18,000 miles per hour); entering the frigid vacuum of space; then reentering the atmosphere at speeds that threaten to break up or burn up the reentry vehicle and its warhead.” The parts of a nuclear missile include several rocket motors, which fall away in stages during flight, and a re-entry vehicle, which houses the warhead and carries it all the way to its destination. The Minuteman III, first deployed 50 years ago, is today America’s only land-based ICBM. Proponents of the GBSD walk a tricky line, trying to convey an urgent need to replace the Minuteman III while trying not to say it is falling apart, which would presumably undermine its deterrent effect. So they refer to the Minuteman system as “aging” and say that while modernization must absolutely happen right now, with ongoing maintenance the current missiles will be completely fine until 2029. How “aged” is the system? The silos were built at the same time as the underground launch control centers. Bosetti described an episode in one of the launch control capsules he frequented in the late aughts, a months-long period with failed sewage pumps. “There was a lake filled with sewage at the bottom of the outer shell, and a 2-foot diameter, 3-foot tall cardboard tube with a plastic bag liner we used as a toilet,” he said. “We'd periodically lug it out to the elevator, where the sergeant upstairs would try to empty it into the sewage lagoon. After a few hours, you'd stop smelling the lake, but that was just a symptom of hydrogen sulfide poisoning. Once they fixed the sewage problems, there was no remediation or cleaning of the capsule shell.” “Even if we're restricting it to pure utilitarian calculations of military usefulness,” Bosetti said, “those capsules and their silos are decades past their design life.”

Proponents of the GBSD walk a tricky line, trying to convey an urgent need to replace the Minuteman III while trying not to say it is falling apart.

Sewage lagoons like this are found at each launch control facility. (Jim Ruddy / National Park Service)

Predictably, as the US Air Force sought better and better nuclear missiles—cheaper and less accident-prone, with ever-improving range, accuracy, and destructive capability—the Soviet Union did the same. In a 1990 study published by the Air Force, the authors wrote that “improvements in Soviet ICBM forces and missile accuracy raised serious concerns over the ability of silo-based ICBMs to survive an attack.” In July 1976, Congress refused to appropriate funds for the Peacekeeper, convinced that the silo-based system proposed for it would make it vulnerable. The defense establishment explored a variety of alternatives to fixed silos, including missiles that could be moved around on train tracks. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter approved a system of “multiple protective shelters,” in which Peacekeeper missiles would be mobile. President Ronald Reagan tried to reverse that decision and base the missile in fixed silos, but Congress again rejected such a plan in 1982. Political battles over the vulnerability of fixed silos continued through the 1980s. Those eager to get new missiles deployed one way or another, like Reagan, eventually solved the conundrum with an intellectual contortion. Defense thinkers began to argue that the susceptible nature of America’s silo-based nuclear missiles was not a flaw but a feature. They redefined the silos as intentionally vulnerable, designed to make Moscow use up weapons. This rationale continues today. “The ICBM force provides a cost-imposing strategy on an adversary,” Mattis explained to a Senate committee in 2017. Because they are meant to draw nuclear attacks like a sponge draws water, military analysts have long called America’s land-based missiles the “nuclear sponge.”

An ICBM launch site located among fields and farms in the countryside outside Minot, North Dakota. (Charlie Riedel / AP)

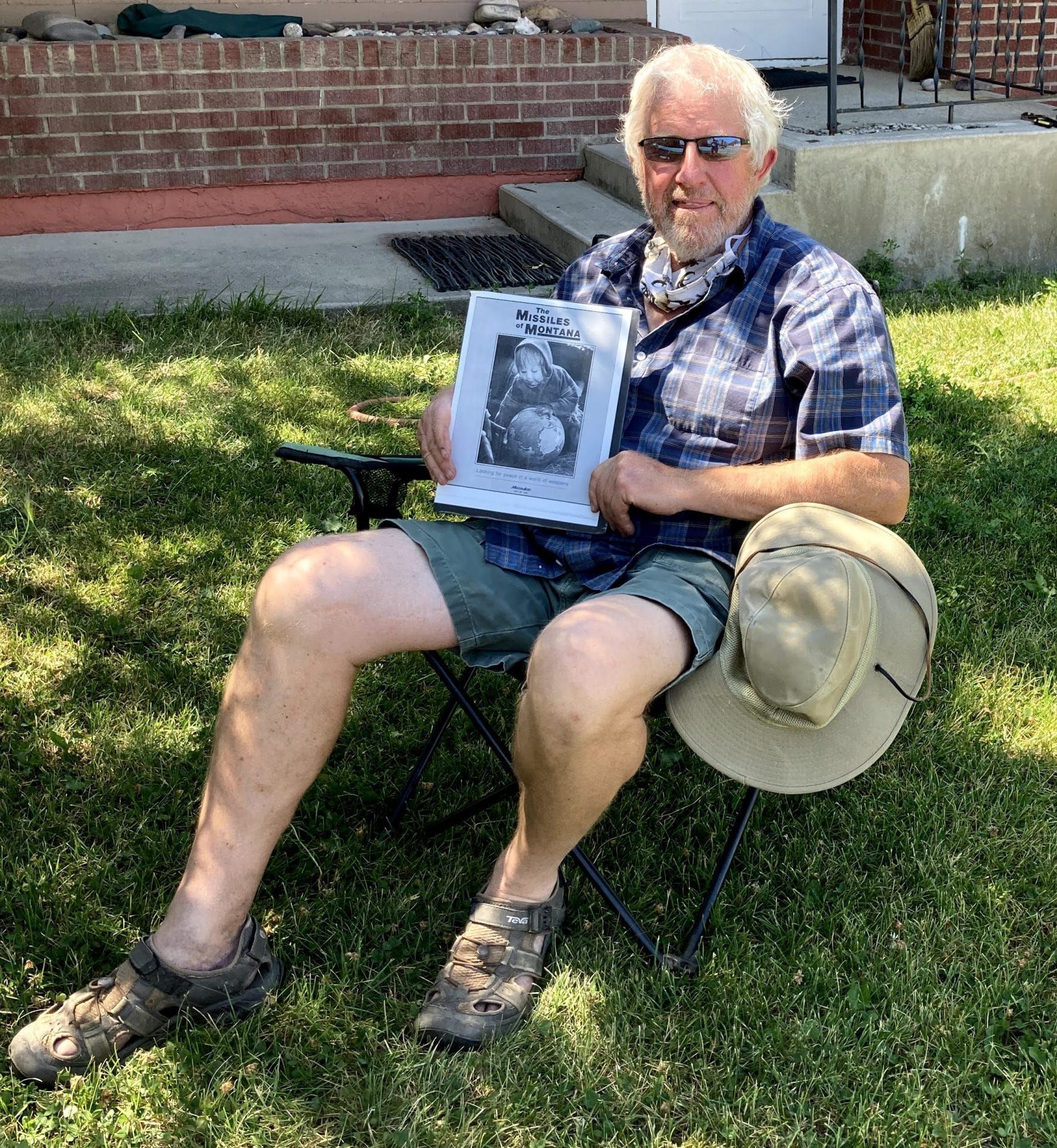

Zane Zell’s grandparents and parents farmed wheat on flat land outside of Shelby, Montana. In the 1960s, when Zell was in high school, the government seized a few acres of the family farm. “The military comes in and says, ‘We're going to build a missile here, so either sell us your land or we condemn it and take it,’” he said in July, sitting in a blue plaid shirt, sunglasses, and a cloth mask in front of his brick house in Shelby. The military fenced off the area and it became Minuteman missile silo Papa One. “A lot of people in this area were in poverty. Either they had no knowledge of the missiles, or didn't care, or they were supportive of them.” As a student at the University of Denver, Zell became involved in the anti-war movement. With his wife and children, he eventually returned to run the farm. He still resented the missile on his land and would perform small acts of rebellion, deliberately driving over a surveying stake or jostling the chain-link fence with his tractor; by the time an airman appeared to see what had set off the sensors, Zell would be on the other side of his field. In the summer of 1982, by which time the US had 1,000 ICBMs scattered across seven states, Zell attended an event in the nearby town of Conrad. There, Missoulans Mark Anderlik and Karl Zanzig gave a presentation on the Silence One Silo campaign, its modest yet audacious goal encapsulated in its name. The two young men were on the lookout for people like Zell, farmers sympathetic to their cause who had missiles on their land. The following summer, Silence One Silo held a several-day “Little Peace Camp on the Prairie” on the Zell farm, attended by about 200 people. Speakers came from around the state. They surrounded Papa One with farm machinery and trucks. Silence One Silo was just one of many efforts: In the 1980s, an anti-nuclear weapons movement bloomed around the world. Organizations of physicians and religious leaders banded together. The Mormon Church opposed a plan to base the Peacekeeper missile in Utah and Nevada.

Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan signing the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty on December 8, 1987 in the East Room of the White House. (Ronald Reagan Presidential Library)

Then the world changed. In 1988, led by Reagan and Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev, the United States and Soviet Union joined the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, the first agreement to ban an entire category of nuclear weapons. With the Cold War over and the Soviet Union in economic shambles, Moscow and Washington made more serious cuts to their arsenals, both through unilateral moves and the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I), signed in 1991, which limited the number of warheads each country could have. The United States silenced not just one, but 550 nuclear missile silos. In 2008, the Air Force declared the Zell farm’s silo inactive. It tractored in a 65-foot transporter erector loader to remove the missile. It blew up the silo and filled what was left with concrete. The fence remains, surrounding overgrown dry grass, a rusting sign warning that it’s still a “hazardous area.” “We didn't physically shut down any missile silo,” Zell said. “The treaty shut them down. But we tried to put pressure politically on our representatives. We tried to bring it to the public's attention.”

Zane Zell outside his home in Shelby, Montana, holding a copy of an April 29, 1984 special section on the missile fields published by the Missoulian. (Elisabeth Eaves)

One nuclear weapon could wipe a mid-size city off the map and kill most of its people. Several nuclear explosions over several cities would kill tens of millions. If 100 detonated over cities, it would likely cause a global nuclear winter, in which widespread firestorms blanketed the world in smoke, blocking out sunlight, lowering the Earth’s temperature, killing off agriculture, and leading to mass starvation. In 1986, governments possessed a spectacularly redundant 64,099 nuclear warheads, the vast majority in the hands of the two superpowers, though Great Britain, France, and China also had a few hundred each. With the arms reductions that followed the Cold War, by the time a fresh-faced US President Barack Obama entered office in 2009, there were “only” 11,410 nuclear warheads in the world. But by then, another worrisome trend was afoot: Whereas at the end of the Cold War, only six governments had nuclear weapons, now nine had them, with India, Pakistan, and North Korea having joined the United States, Russia, China, France, Britain, and Israel. With more components and fuels in more places, experts worried that not only rogue nations but even a terrorist group might be able to build a crude nuclear weapon. On a sunny morning in April 2009, Obama gave a speech to tens of thousands of people in Prague. He observed that “in a strange turn of history, the threat of global nuclear war has gone down, but the risk of a nuclear attack has gone up.” He pledged his country’s commitment to a world without nuclear weapons, and went on to negotiate New START, signed in April 2010, limiting the United States and Russia to 1,550 deployed strategic warheads each. (Today New START is the only remaining treaty limiting the two countries’ nuclear arsenals; Russia and the United States agreed to extend it for five years late in January.) Obama’s efforts to reduce nuclear arsenals were the main reason he won the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize.

Barack Obama's Prague speech on April 5, 2009 was his first major foreign policy address. (EURACTIV)But by late 2010, the president was in a bind. To be ratified and go into effect, New START needed 67 Senate votes, and Obama’s Democratic Party had only 59 seats. Arizona Senator Jon Kyl, who as Republican whip influenced how fellow party members voted, had opposed nuclear weapon agreements in the past. In May, the White House submitted a congressionally mandated report (known as the “section 1251 report,” after a section of that year’s National Defense Authorization Act) in which it outlined a 10-year, $180 billion scheme for maintaining and modernizing nuclear weapons. For Kyl, that wasn’t enough, and the Arizona senator spent much of the year pressuring the administration to commit more funds to modernization. He threatened to withhold support or delay a vote on New START. When Democrats lost seats in a mid-term election, Obama knew that if the New START vote was delayed until the next session of Congress, chances of ratification would be even worse. As the carrot to his stick, Kyl implied that he could be persuaded to vote in favor of ratifying New START. For instance, in a July 2010 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, he wrote that most senators would likely consider the nuclear treaty “relatively benign” as long as Obama committed enough money to nuclear modernization. Kyl kept up the pressure until the White House updated its 1251 report in November, adding another $5.4 billion for nuclear modernization, including $4.1 billion to be spent between 2012 and 2016. Just two days before the Senate vote, less than a fortnight before the end of the session, Obama made a pledge to four key Republican senators, writing a letter in which he said that “nuclear modernization requires investment for the long-term,” and “[t]hat is my commitment to the Congress—that my administration will pursue these programs and capabilities for as long as I am president.” His efforts at persuasion worked. On December 22, 71 senators, including 12 Republicans, voted to ratify New START. Kyl, after dangling the possibility of his support, was not among them. Obama had his foreign policy victory. The United States and Russia would cut back on warheads. But it came at the cost of committing extra billions to nuclear modernization, which helped pave the way for the GBSD.

Legislators, real-estate developers, and industry leaders broke ground on Northrop Grumman's headquarters for GBSD development near Hill Air Force Base in Roy, Utah. No military officials were present for the August 27, 2019 ceremony. (Northrop Grumman)

Kathy Warden, speaking at a cybersecurity summit in 2016. She was appointed CEO of Northrop Grumman in January 2019. (Northrop Grumman)

In August 2019 in the suburban city of Roy, Utah, 11 people grabbed shovels and lined up for a group photo next to a long pile of dirt. Behind them, the Wasatch mountains shimmered in the summer heat. The lineup included two real estate executives, four corporate leaders, the president of the Utah Senate, two of Utah’s four members of the House of Representatives, and the state’s two senators, Mike Lee and former Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney. Though the empty lot in which they stood adjoined Hill Air Force Base, there were no military officials among the group. Lee and Romney flanked the central figure like bishops in a game of chess, but in place of king and queen stood just one person, Kathy Warden, chief executive officer of Northrop Grumman, her red jacket vivid against the men’s blues and grays. They were there to break ground on a Northrop Grumman building, the company’s GBSD command post, though it had not yet won the contract to build the weapon. Romney touted the “high-skill, high-paying jobs” the project would bring to his state. The GBSD had recently survived a defunding attempt, when, in July 2019, Oregon Democratic Rep. Earl Blumenauer suggested an independent study on extending the life of the Minuteman III and delaying its replacement. But his proposed amendment to the defense authorization bill was voted down. Raised in small-town Maryland, Warden has an MBA from George Washington University and early in her career worked for General Electric as a senior manager in commercial industries. She has said in interviews that the 9/11 terrorist attacks prompted her to change professional tracks and switch into defense. “I wanted to create a world that was a safer place for my son to grow up in,” she told her university alumni association last year. “That is what made me make a professional change but also for the past 17 years, is what kept me in this industry because I feel like I’m doing something to contribute … to impact the world in some small way.” After a stint as vice president of intelligence systems at the defense giant General Dynamics, she joined Northrop Grumman as head of its cybersecurity division in 2008. In January 2019, she ascended to the top role.

A view of the Northrop Grumman Roy Innovation Center under construction in December 2019. (Cynthia Griggs / US Air Force)

Construction workers toiled on the new Northrop Grumman building next to Hill Air Force base for more than a year. During that time, as CEO, Warden participated in quarterly earnings conference calls with investors, and in every one, someone asked when she expected the big contract. In the fall of 2019, analysts asked her if either a Federal Trade Commission investigation or competition from Boeing might affect the process of awarding a GBSD contract. Each time, she said she expected a deal by the fall of 2020. She made no mention of the upcoming presidential election, but everyone knew that a new administration or significant turnover in the senate could derail the GBSD if it wasn’t a done deal. Investors also quizzed her about “CapEx,” or capital expenditures, which are funds a company uses to acquire physical assets like buildings. In the January 2020 earnings call, Warden said she expected the company to spend $1.35 billion on capital expenditures in 2020, a figure inflated due to the GBSD, though she didn’t say by how much. With the new Utah property, the company was clearly spending a lot on a project it hadn’t yet been hired to do. In May of 2020, Warden spoke at the Bernstein Strategic Decisions Conference, an annual investors’ event, held virtually to accommodate the pandemic. She answered questions in front of a Northrop-logo backdrop while a Bernstein analyst asked questions from a home office. In March, the federal government had passed the CARES Act, spending $2.2 trillion to try to rescue the economy from the impact of the pandemic. It was considering another bailout package. The analyst asked, delicately, if the health crisis threatened to slow down the GBSD: “Some people have speculated that, GBSD being a very large long-term program, if there is budget pressure … Are you seeing any evidence of that as a possibility, that this could take a little bit longer to push through development than perhaps we had thought?” “We're actually seeing quite the opposite focus, a focus on schedule and the importance of getting through the engineering phase of this program on time,” she replied. “It is important that we both get started now.” In early July, the House Armed Services Committee debated the defense authorization bill for 2021 in a late-night session. By this time, the coronavirus had shut down huge swathes of the economy, and the United States was identifying 50,000 new cases per day. House members wore masks and sat scattered from one another in a cavernous committee room. Ro Khanna, the California Democrat who represents Silicon Valley, made a pitch from a video screen. He proposed an amendment that would transfer $1 billion—or one percent of the missile’s projected cost—away from the GBSD and into a pandemic preparedness fund. In the ensuing discussion, Republican Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming, home of F.E. Warren Air Force Base and the city of Cheyenne, which like Great Falls anticipates a GBSD windfall, countered her colleague with a string of non-sequiturs. She said the Chinese government had caused the global pandemic; that Congress needed to “hold the Chinese government accountable for this death and devastation;” and that Khanna’s plan would benefit the government of China. “It is absolutely shameful in my view,” she said of his proposal. “I don’t think the Chinese government, frankly, could imagine in their wildest dreams that they would have been able to get a member of the United States Congress to propose, in response to the pandemic, that we ought to cut a billion dollars out of our nuclear forces.” Khanna’s proposal was voted down. The House went on to pass a defense authorization bill worth $741 billion, including $1.5 billion for the GBSD to be spent in 2021 alone. Of course, defense companies don’t expect politicians to vote for massive defense spending without encouragement, and their efforts at persuasion take several forms. First, they hire their former clients, retired military leaders. In a 2018 report, the Project on Government Oversight, a non-partisan watchdog, counted 24 former senior defense department officials who were employed at that time by Northrop Grumman. Second, defense contractors give money to elected officials, though not directly. A company’s employees, executives, and their family members may donate to political campaigns, as may the company’s Political Action Committees, or PACs, which are organizations set up for the purpose of making such contributions. The non-partisan Center for Responsive Politics tracks campaign contributions by industry, tallying how much each corporation gives via these two proxy methods. The total amount the defense aeronautics industry gave to national politicians rose steadily from $8.4 million per two-year election cycle in 1990—as the Cold War ended—to a new peak of $35.3 million in the 2020 cycle. The money is liberally distributed, going to both Republicans and Democrats—51 percent to 49 percent in 2020—and spread among many campaigns.